The battle for the jus soli

11 May, 2021

Following the proposal by the Italian politician Enrico Letta, who recently became secretary of the Democratic Party, the debate on jus soli – namely the birthright citizenship, which allows anyone born in the territory of a State to nationality or citizenship – has been renewed in Italy. A new law for jus soli would be crucial for hundreds of thousands of children and teenagers that live in the country since birth but without having obtained citizenship yet. Right-wing political parties, like Lega Nord and Fratelli d’Italia, have for years strongly opposed to this law, arguing that it has not been adopted by any other EU country, which is firstly erroneous and secondly misleading. Worldwide, numerous states have passed laws recognising jus soli within their territory. For example, a study by the Global Citizenship Observatory showed that this way of acquiring citizenship is used by 83% of states in North, Central and South America. Among the most populous states, we can cite the United States, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. This means that anyone born on the soil of these states is entitled to citizenship, and is therefore not, at least de jure, discriminated against in this respect. Within the EU countries, the situation is, though, rather different.

The current situation in the European Union

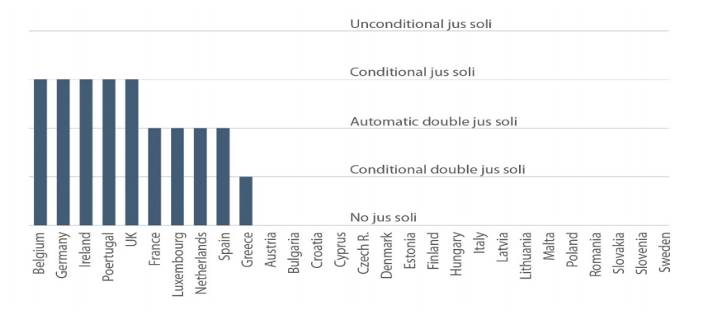

Before analysing the differences among the Member States, it is important to briefly recall the different ways of acquiring nationality in a state. As stated by the European Parliament, “two major modes of acquisition of citizenship (nationality) exist: acquisition of citizenship at birth, either by descent (jus sanguinis) or by birth in the territory of a country (jus soli); and acquisition of citizenship through various naturalisation procedures”. The most common form of acquisition of citizenship is jus sanguinis and none of the EU states grants automatic and unconditional citizenship to those children who are born in their territories from foreign citizens. There are, however, more restricted laws that are in a way closer to the concept of jus soli. In particular, 5 EU countries have such rules of conditional jus soli: Belgium, Germany, Ireland, and Portugal[1]. The so-called “conditional jus soli” is applied bearing on the condition that the parents have resided in the country for a certain period of time before the child’s birth. The minimum parental residence is required by Ireland (i.e. 3 years), while the longest is in Belgium (i.e. 10 years).

In other EU countries – France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain – children born in the country from foreign citizens can acquire citizenship at birth if at least one of their parents was also born in the country (this case is called “automatic double jus soli”). In Belgium and Greece, instead, citizenship can be acquired through “conditional double jus soli”, for which there are different criteria if compared to the “automatic double jus soli”. While in countries like France, Spain and the Netherlands the acquisition is automatic, other State have additional requirements: Belgium requires five years of prior residence for parents, while Greece the permanent residence status for parents. It must be pointed out that some of the states considered offering different forms of jus soli: for example, Belgium and Portugal have both rules of conditional and conditional double jus soli. The chart shows the most inclusive form of jus soli that the various Members have.

Figure 1 – the most inclusive rule of jus soli applicable in each EU country.

Source: European Parliament 2018

Data source: Global Database on Modes of Acquisition of Citizenship, GLOBALCIT

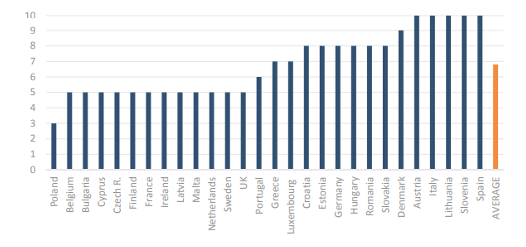

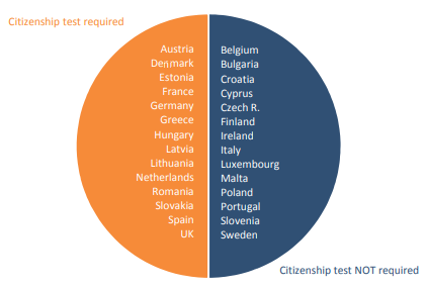

In countries where these jus soli laws do not exist, the acquisition of citizens must be asked by the individual after birth, most commonly based on the period of residence in the country. This time range can go from 10 years, the maximum required in countries like Italy, Spain, and Austria, to 3 years, the shortest period in EU required by Poland. The chart Figure 2 shows the period of residence that individuals must prove in order to acquire the citizenship. Another requirement can be the so-called “citizenship tests”, in which candidates can prove their knowledge about the country, its legal and constitutional system and general cultural values. This requirement is present in half of EU countries.

Figure 2 – Minimum period of residence required for naturalisation in EU-28; Figure 3 – citizenship tests in EU-28.

Source: European Parliament 2018

Data source: Global Database on Modes of Acquisition of Citizenship, GLOBALCIT

Source: European Parliament 2018

Within the EU Member States there are endless specifications and peculiarities about the possibilities to acquire citizenship along with various paths that individuals can follow to achieve this goal, as different countries and also different legislations can request various things to migrants. However, it is really important to bear in mind, given the subject we have been dealing with, that numerous countries apply further limitations for children born of foreign parents. In Italy, for example, a child born to foreign parents may apply for citizenship only after reaching the age of 18 and if he or she has resided in Italy ‘legally and continuously’ until then. This means that children born on Italian soil have to depend on their parents’ citizenship until they reach the age of majority. This is clearly problematic, for example because the loss of the parents’ citizenship would have very serious repercussions on the children. It should however be pointed out that the only law that comes close to jus soli in Italy is the one that grants Italian citizenship to a person whose parents are unknown or stateless or do not transmit their citizenship to their child according to the law of the State of which they are citizens; it can be also given to the child of unknown persons who is found abandoned on Italian territory and whose citizenship cannot be determined.

The Italian scenario as a reference

Currently, the two main draft laws on citizenship in Italy are still blocked in the Senate, following dozens of amendments that have been brought forward by right-wing parties. The proposals included, on the one hand, a moderate jus soli, according to which a child of foreigners can obtain the right to citizenship if at least one of the two parents is legally in Italy with unlimited right of residence or EU residence permit; on the other hand, the so-called jus culturae, where foreign minors born in Italy or arriving before the age of 12 who have regularly attended at least 5 years of training in school may apply for citizenship.

Several political figures in the country put forward various reasons against a law on jus soli. One can cite, for example, the fact that taking Italian citizenship would also give access to EU citizenship and that, therefore, consultation at the European level would be necessary. Alternatively, some have highlighted the fact that it would be more important to have the minimum level of cultural background necessary for the complete integration of the applicant. Or, it is argued that fundamental rights are protected in any case and therefore such a radical law is not necessary. However, the reasons for the yes vote seem more than obvious when considering the implications for hundreds of thousands of people. Current laws do not allow foreign children born in Italy to enjoy the same rights as Italian children. For example, they cannot join sports leagues where there are restrictions on foreign players, as nationality is a criterion required to be included in national teams. They cannot go abroad through scholarships for a study experience longer than twelve months, they cannot vote or take part in many public competitions. They cannot visit Montecitorio, the seat of the Chamber of Deputies of the Italian Republic. Some represent relatively small concerns, others are more relevant, but they are all aspects that contribute to differentiation and marginalisation between children of Italians and children of foreigners. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, children are dependent on their parents’ citizenship and this can often be problematic if their citizenship is suspended or problems arise for their parents.

A glimpse into the future

As pointed out by Giovanna Zincone, professor of political sociology, Italy, like all countries with a high number of emigrants, preferred the transmission of citizenship through jus sanguinis to maintain a link with the many Italian emigrants who lived and worked abroad and contributed to the development and enrichment of the country through remittances. It therefore seems paradoxical that the descendants of Italians who have emigrated abroad (e.g. to the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Uruguay, Australia, etc.) can apply for recognition of Italian citizenship jus sanguinis, while children born in the country and who have always lived there have no access to it except after lengthy administrative procedures and after reaching the age of majority. Hundreds of thousands of children and adolescents are waiting for a law that will protect their rights and finally see them as citizens of the nation where they were born, where they grew up, where they studied and where they have been living for years and years. It would be necessary to rethink the set of laws that establish the acquisition of citizenship in Italy, and in all those countries where there are still no jus soli mechanisms, so as not to further discriminate against all those people who do not have citizenship and who, as a result, do not some of their potential rights respected. On the contrary, the reception and integration of these individuals could bring great added value to the rest of society.

[1] The fifth country was the United Kingdom, which is no more part of the European Union.