Reimagining Care: Feminist degrowth and UBI

28 September, 2021

In 1975, the women of Iceland gathered together to plan a “women’s day off”, meant to highlight the essential contributions women make to Iceland’s economy and social-well-being. The main goals of the strike were not only to protest the pay discrepancies between men and women, but also the low value that has been placed on women’s work both inside and outside the home. About 90% of Icelandic women participated in the strike, resulting in much of the country more or less coming to a standstill. The following year, the Icelandic parliament passed a law guaranteeing equal pay between men and women. Though Iceland is today largely considered to be one of the most gender-equal countries in the world, it is still by no means free from inequality.

The story of Iceland is meant to emphasize the vital contribution that women make to our societies, not only in the labour market, but also through the invisible labour that they perform at home and in care facilities. Long before the pandemic, the crisis of care was acknowledged by many feminists to be a structural problem that reveals just how interdependent our society is, especially in terms of the work that is being done to care for others. It must also be said that migrant women and women of colour bear an even greater burden, as much of the care work previously performed by white women has now been outsourced to them. The ongoing pandemic has further exposed the burdens borne by underpaid care workers, the limits of dual earner households and the lack of investment in care infrastructure.[1]

Within the European Union, proposals to reconceptualize the care economy have been put forth by the European Women’s Lobby and other organizations, who have praised the European Commission’s new Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 for including this issue and consider this an important starting point to eventually develop a Care Deal for Europe. However, more ambitious policies are needed in order to remove the burden of unpaid and underpaid care work from women’s shoulders and distribute it equally. Due to the demographic shift that will occur as the EU’s population ages, considerable demand will be placed on the care sector, making the need for changes within this system all the more pressing.

Rethinking the care sector has long been a topic for feminist economists within and outside of Europe – they stress the need to challenge our traditional understanding of work, production, and how the current growth paradigm systematically devalues the care sector. This has led to the emergence of a relatively new feminist degrowth approach, which puts care work and the reproductive economy at its centre, recognizing and strengthening its importance and the need for transformative policies that acknowledge it accordingly. The main issue with the EU’s current proposal is that they do not necessarily target the unequal gender relations that persist within and without the care economy and how they can be broken down. In the words of renowned economist Kate Raworth “The great mistake of economics is thinking of the economy as separate from the society of which it is part and the environment in which it is embedded.”

Inequalities within the Care Economy

Care work most often operates outside the traditional economic sphere, i.e. being relegated to the domestic sphere, where its importance is diminished and rendered valueless. This work is often seen as intrinsically different from other forms of labour due to the interpersonal and emotional relations between subjects and the inherent vulnerability that can exist between those receiving care and those providing it, which again is regarded as a ‘feminized’ task. According to EIGE, the care economy can be defined as “part of human activity, both material and social, that is concerned with the process of caring for the present and future labour force, and the human population as a whole, including the domestic provisioning of food, clothing and shelter.” As mentioned, feminist economists were the first to argue for the recognition of the essential nature of this ‘unproductive’ care work, which includes not only domestic work, but also child and elderly care.

Social reproduction, that allows for the generation and renewal of human life and thus the labour force, is at the centre of this feminist interpretation of the economy. It acknowledges the unpaid care work mainly conducted by women is equally valuable to the paid labour traditionally recognized by the labour market.[2] In this sense, the labour force is maintained through the caring activities (childcare, healthcare) that are conducted by women, the set of daily and generational tasks that allow for the continuation of life. Over the last four decades, more women have entered the workforce, prompting a decline in the male breadwinner-female homemaker model.

However, despite increased participation by women in the labour market, they are still carrying out the majority of both unpaid and paid care work. According to the ILO, women globally spend about three times as much time than men on these tasks, around 76.2% of total hours of unpaid care work. As a consequence of the devaluation of care, paid care work has generally been seen as ‘women’s work’ and is often significantly underpaid, despite requiring many interpersonal skills and being extremely critical for the well-being of individuals and society. The European Union has sought to address these issues and implemented minimum standards when it comes to care but falls short when it comes to more innovative policy proposals that focus not only on labour market participation and childcare but centring the economy around care.

For example, in 2002, the European Council adopted the Barcelona targets, which recognized the need for affordable and high quality childcare facilities in order to encourage women’s labour market participation. These targets have unfortunately still not been met. Additionally, in 2019, the Work-Life Balance Directive entered into force; this piece of legislation sets minimum standards for Member States to achieve equal sharing of parental leave between women and men and to address the lack of representation of women in the labour market. This includes the use of European funds to enhance care services, “ensuring protection for parents and carers against discrimination or dismissal and removing economic disincentives for second earners within families”. The new Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 focuses on the provision of childcare services, improving upon the Barcelona targets, but ultimately does not go far enough in addressing structural inequalities such as the gender pay gap. The gender pay gap not only relates to pay discrepancies between genders, but the fact that many ‘traditionally’ female occupations are devalued and thus paid less – care work being a prime example. As can be seen, these proposals do not dive into addressing the structural inequalities surrounding care work, which will become even more crucial as Europe’s population continues to age. The available data regarding care work highlights the pervasiveness of these inequalities, which are present in every single Member State.

Despite these efforts, 92% of women within the EU are regular carers and 81% are daily carers. In contrast, men are at 68% and 48% respectively. Though labour market participation of women has increased as women became more emancipated, in many households’ gender roles continue to persist, leaving them to perform the tasks that have been deemed inherently feminine. This holds true for dual-earner households as well as single-earner households. The time dedicated to these care tasks also varies amongst Member States, though not a single one has men participating at a higher rate than women. This can be explained by the differing care regimes that are in place amongst the various EU countries, with those continuing the traditional and more conservative care model (based mainly on gender stereotypes) also having larger gender inequalities.

These gaps in care occur not only between Member States, but also within different groups of workers themselves, due to factors such as marital status or number of children. Women in lower paying jobs face an even greater double burden of care work, which then decreases as income rises. This is due to lower-income women not being able to afford outsourcing this work to others (mainly other women) or not having access to childcare facilities. This correlation between time spent on care tasks and changes in income is not as apparent for working men. Additionally, the ability to outsource this care work, as done by higher income households, is simply not a possibility, in turn creating inequalities not just between men and women, but between households as well.

Thus, the disparities between men and women within the care economy persist, in spite of the well-intentioned proposals of the EU. Many of the policies tend to focus on people in employment or simply supporting women’s employment, when the root of the issue must be targeted through transformative policies that advance gender relations and how care work is distributed within families. Repositioning the role of care has long been a goal of feminist scholars, who are playing a more decisive role in other emerging movements as well.

A Feminist Degrowth Perspective

Degrowth stresses the need to move away from economic growth as a sole political objective. Instead, the focus should be on “well-being, social justice and ecological sustainability”. Within the degrowth movement, the feminist perspective is slowly becoming more prominent, with the Feminisms and Degrowth Alliance (FaDA) network launching in 2017. Feminist scholars have criticized capitalist production and consumption patterns for not taking into account the invaluable nature of care work for individual and societal well-being. This approach specifically envisions a society with diverse gender roles, where paid and unpaid work is distributed fairly among all members of society.

Degrowth carries potential to rethink the growth-centric economy and lends itself well to feminist economic thought, which seeks to undo patriarchal power structures, which in turn alleviates the undue double burden placed on women at home and in the labour market. Indeed, Kallis, Demaria and D’Alisa have stated that “the degrowth imaginary centres around the reproductive economy of care”[3], with other central proposals of the degrowth school (e.g. work-sharing) emphasizing care as well.

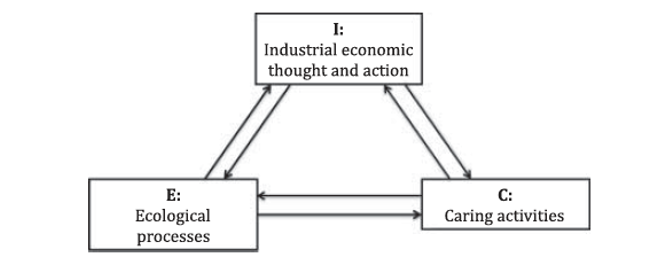

Corinna Dengler and Birte Strunk have examined the impact of the current growth paradigm on gender and environmental injustices. Their analysis is based around the ICE model developed by Jochimsen and Knobloch (see Figure 1) which relegates caring activities and ecological processes into the ‘maintenance’ economy, which the formal ‘monetized’ economy largely ignores. Dengler and Strunk’s analysis acknowledges that an increase in women’s labour participation will not necessarily further gender equality. As examined, this creates a double burden of paid and unpaid work for most women, and even when this work is outsourced to care providers, there still exists a divide, but now between the more vulnerable and those who profit. Thus, Dengler and Strunk suggest work-sharing proposals that focus on the working day rather than working week. Since women are most often the ones that are in charge of daily household activities (e.g. caring for other family members), a shortening of the “first shift” for both women and men could allow for a reduction in women’s double burden and a more equal division of these daily activities amongst genders. Though by no means flawless, this proposal is meant to emphasize the potential for feminist economics and the degrowth movement to pave the way for a caring economy and potentially alleviate certain gender injustices.

The feminist degrowth movement is centred around regeneration – in this sense policies geared towards reforming the care economy are meant to encourage this sector to thrive. In order to do so, redistributive measures should be introduced to ensure that carers are adequately compensated. Consequently, both feminist scholars and degrowthers have been examining UBI (Universal Basic Income) as a potential alternative. Feminist degrowthers have more specifically supported a Care Income that builds on basic income proposals and emphasizes the recognition of unpaid care work performed by women.

Universal Basic Income through a feminist lens

A Universal Basic Income (UBI) has been supported by degrowthers, with the feminist branch specifically calling for a Care Income as proposed by the

Global Women’s Strike and taken forward by the Green New Deal for Europe. This involves the payment of an unconditional regular income paid to adult members of societies, regardless of work status, level of income or living arrangements. Though convincing arguments in favour of a basic income scheme have been made, it has yet to be fully introduced into any modern welfare state due to the objections that it undermines the incentive to work and unsustainably increases public expenditure.[4]

One aspect that needs to be considered in the debate on basic income is its effect on the working habits of women and men. Feminist scholars have argued that basic income has the potential to help address the inequalities that persist between men and women within households and families. More often than not, social protection programs within countries reference households rather than individuals, not reflecting the inequalities that many women face – even if on paper the household is ‘well-off’.[5]

Ailsa McKay, Carole Pateman and other feminist economists have pointed to UBI as a method of not only influencing the gendered division of labour within households, but also benefits such as providing economic independence for women. Given that women within the EU (and globally) are at a higher risk for poverty, a fixed income could alleviate not only economic concerns, but also improve the psychological health and well-being of women. This is due to the recognition of their work as a valuable part of the economy. The use of this income as a form of social protection is especially true for women in abusive relationships, as receiving an independent income would potentially enable them to have the financial security to leave (though this does not account for the myriad of other factors that may prevent women from leaving abusive partners).

A main concern with this proposal is that instead of enabling more women to enter the labour market, they instead continue to perpetuate the caregiver role and exit the labour market completely, while men continue to free-ride on their unpaid domestic work. As Pateman argues, democratization must be included in debates on UBI; meaning “women’s freedom and standing as citizens” must be recognized as well. Thus, it should be noted that UBI is not a panacea – due to the deeply entrenched patriarchal norms about men and women’s roles in productive and reproductive work (which then become institutionalized norms), introducing a basic income will not suddenly overcome this challenge. Within the EU, the Universal Basic Income proposal is still a topic of debate. Though well-known philosophers and economists such as Philippe van Parijs have endorsed the idea, the main fear relates to its effect on the labour market. At present, the proposal has gained more traction due to the inequalities further exposed by the pandemic.

Caring for Europe

The new Gender Equality Strategy launched by the European Commission recognizes the structural inequalities present in care work, stressing the importance of moving away from gender stereotypes at work and in the home and will “address the inequalities built into some national tax and benefit systems and their impact for second earners”. This strategy is a step in the right direction in negotiating a new care deal for Europe and integrating care into its macroeconomic strategies as well. Its focus on childcare provision has left the Strategy wanting in other areas, such as working hours and gender pay gaps, and simply does not place care at the centre of its economic activities.

The European Women’s Lobby (EWL) has been at the forefront in advocating for rethinking the European economy through a gendered lens, labelling their proposal the “Purple Pact”. It argues for a shift in the current macro-economic framework of the EU, whose gender-blind approach has negatively impacted not only women but also the natural environment. Monetary, fiscal and tax policy that turn a blind eye to issues of gender can affect employment opportunities, reduce policy budgets targeting gender inequality and increase the demand placed on women for unpaid labour. For example, reducing budgets for social programmes (like care services) leads to more women having to pick up the slack. EWL considers caring for others and being cared for an essential part of their feminist economic model, as “care is a collective need that requires a collective responsibility”.

Included in their macroeconomic proposals is not only to include more feminist economists in order to ensure equal representation in economic decision-making, but also the exploration of degrowth strategies. In terms of the care economy, more research needs to be conducted on this sector, which in turn can be published and promoted to garner more understanding and recognition of its importance. The work of EIGE on monitoring the EU’s action on this issue and providing recommendations on how to put care at the centre of EU policy making will be beneficial for future work on this matter. Not only does their research stress the need for a revaluation of care work, but it also demonstrates how deprioritizing care work affects both the economy and society, especially in times of crisis. Member States must work towards implementing the Work-life balance (WLB) directive, which modernizes the EU legal framework to “encourage a better sharing of caring responsibilities between women and men.” Though limited, especially in its approach to the care economy, its implementation does show progress on the front of gender equality in Europe.

Conclusion

What it comes down to is not simply the implementation of policies that target the gender pay gap or how to increase women’s participation in the labour market; the overarching issue is how women themselves are represented within our society. Despite the progress made, the social norms that both place women in caregiving positions and at the same time devalue its importance are the driving forces that underscore the problems relating to the care economy. Feminist degrowth and feminist economic perspectives understand the inherent value of the work that is being done by women in carrying out both paid and unpaid care work; and their rethinking of the economy includes rethinking how our environment must evolve too.

The pandemic has made it all too clear just how much this double burden of care and work falls unjustly onto the shoulders of women. Urgent remedial measures as proposed here need to be enforced, or we face the risk of women’s already endangered economic status being set back. The prevailing movements discussed above provide hope for a compensated and fulfilled care economy – if mainstream economists are willing to lend an ear.

[1] Dowling, E. (2021). The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It?

[2] Bauhardt, C., & Harcourt, W. (2018). Feminist Political Ecology and the Economics of Care: In Search of Economic Alternatives.

[3] D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., & Kallis, G. (2014). Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era. Routledge.

[4] Standing, G. (2017). Basic income: And how we can make it happen.

[5] Ibid.